Marketing for industrial products exists since the last three decades of the 19th century. For 150 years, manifold ideas have been developed about how management and marketing should be done. All of these ideas might be justified within their historical contexts (and one should know them), but times permanently change. Marketing education means to be prepared to get rid of historical recipes. If you think for instance at famous ideas created for better marketing, do you always remind the historical context for which they have been developed? Marketing education is enabling to switch to contemporary approaches and knowing why past concepts have to be overcome.

A Brief Overview of the History of Marketing Concepts

– We do not support any of them. But you should be familiar with them –

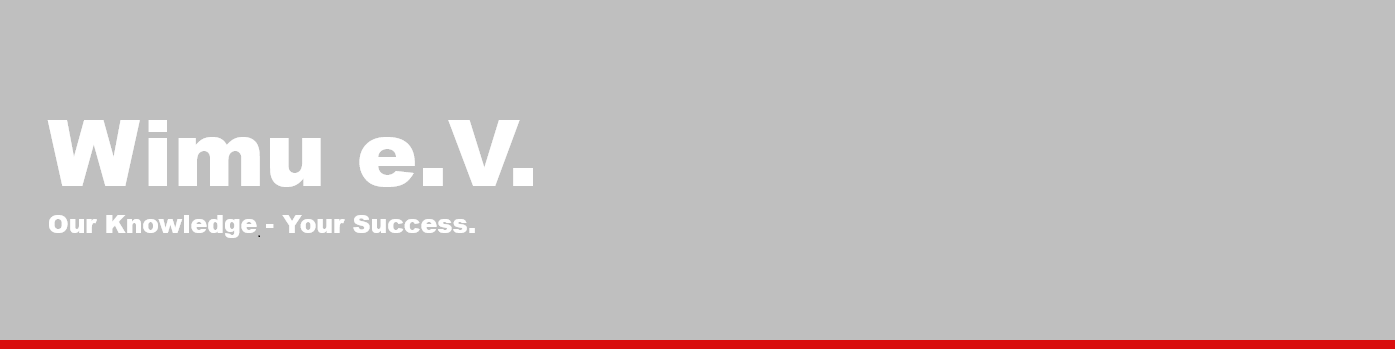

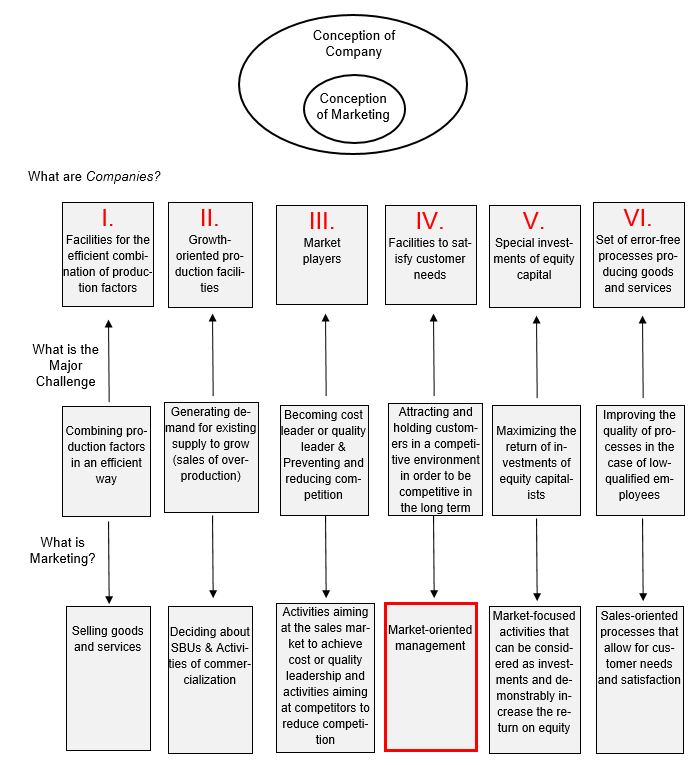

Company as Place of Combination of Production Factors

The post-war period until the mid-1960s was as a period in which demand for goods and services exceeded their supply. A VW Beetle had several months delivery time, there were only a few product variants (for example, in the categories of bakery, bicycles, or textiles), and private households and businesses aimed to satisfy their fundamental needs for goods and equipment. Companies were thought of as a kind of cycle: materials, employees, etc. are procured, so that goods could be manufactured or service capacity could be created; then, finished products could be sold to customers, resulting in revenues that again makes procurement of resources, payment of employees etc. possible. Overall revenues should be higher than overall costs associated with procurement, production, interest on borrowed capital, etc.

Following this view, marketing was limited to sale (labeled in Germany as “Absatzwesen”), i.e., on accepting/rejecting and processing of customers’ orders, to some activities in the field of sales promotions and corporate design, and the engagement of sales people. Marketing was not involved in decisions about products and prices. Instead, cost accounting (Eugen Schmalenbach 1908) was used for calculating sales prices. The primary question that management had to answer in these decades was as follows: How can we transfer the right materials, products and people to the right places and at the right time in the right amount (number) and quality (qualification), both internally and externally, at low cost (and therefore profit-driven)? In this period, management scientists discussed concepts of factor allocations such as Cobb-Douglas functions (Charles W. Cobb and Paul H. Douglas 1929), applied “principles of marginal analysis,” and relied on the presumption that operations research techniques will provide good solutions for challenges. This concept of management can be visualized as follows.

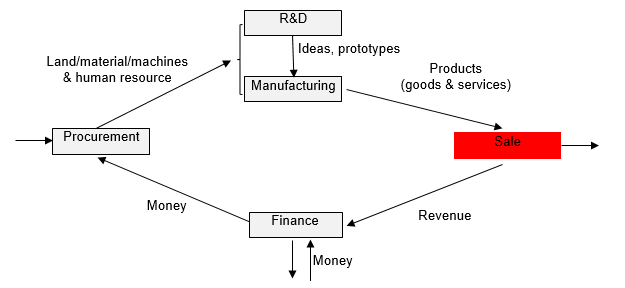

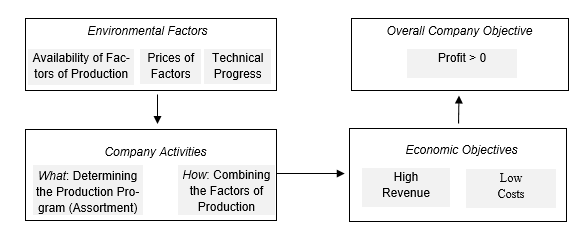

Company as Growth-Oriented Production Facility

In the 60s and 70s, managers were driven by desire for growth. Economists promised society prosperity through growth. It was the time of the German “Wirtschaftswunder”. Management focused on the growth of production capabilities. Growth had a value it itself („We want to become # 1“). Not surprisingly, growth orientation of the majority of companies resulted in two severe problems. The first problem was overproduction and as a consequence oversupply. The customers were not asking for these quantities. For instance, agriculture produced a landscape of “butterberg” (butter mountain) and “milchsee” (milk sea). Due to overcapacity, customers switched into the more powerful position compared to the sellers and could exert pressure to get lower prices and improved product features. The second problem was associated with negative “external effects” on ecological environment (what was already criticized by the Club of Rome at this time) and exploiting resources in developing countries. Nuclear power and plastic materials were promoted in these decades. A new concept of marketing emerged. Managers began to consider strategic and instrumental levels of activities. And the concept of marketing was broadened.

The tasks of marketing were broadened because companies were exposed to a new challenge. They had to find answers to the question “Where and how can I better sell my products?“, and marketing was thought to provide solutions.

On the strategic level, there were four major developments that influenced marketing. First, Harry I. Ansoff (1965) suggested to consider different strategies to achieve growth: growth through entering new markets or growth through developing existing markets. Second, consultants re-invented the cost experience curve (Bruce D. Henderson 1973). The concept suggested the following. If production volume is growing, there will be lower unit costs of production. This enables lower sales prices. Products’ prices become more attractive resulting in higher market share and increased profit. Third, the Boston Consulting Group (1972) proposed implementing a balanced portfolio of so-called dogs, cows, stars, and question marks (i.e., product-market combinations or strategic business units). Fourth, this period fostered thinking about success factors (e.g., Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman 1982) which enables companies to become “excellent.” For instance, the PIMS project (1960-1983) was designed for identifying such factors of financial company success. On the instrumental level, two important innovations were made. First, marketers considered the adoption of the view of Jerome McCharthy (1964) who proposed that marketing should be composed of four 4Ps: decisions about products, price, place, and promotions. Thus, marketing became at least partly responsible for decisions in all of these areas. The second innovation was associated with the belief that marketers should have a bag of tricks and knowledge about seducers how to sell products consumers do not need or want. Very influential were the ideas of Robert B. Cialdini (Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion) which has origins in early consultants such as Edward L. Bernays (“Propaganda”) and Claude C. Hopkins. By using this revised view of marketing, companies should be enabled to sell surplus volume of production by persuasion, i.e., by measures of seduction.

Company as Market Player

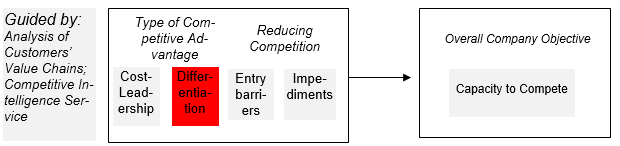

In the 80s, competition among companies further increased. Thus, managers did not only look at consumers and ways how to increase sales through attractive products and prices. They also started looking more intensely to competitors and ways how to reduce their competitors’ sales. The major questions that had to be answered were as follows: “How can we gain a competitive advantage and how can we reduce competition?” In this period of time, the publications of Michael E. Porter gained strong attention (Porter 1980: Corporate Strategy; Porter 1985): Competitive Advantage). His concept of management was focused on reducing competition.

Porter suggested that companies have to decide whether they either want be to cost leaders which enables companies to sell products at very low prices or whether they want to execute “value activities” in such a way that the (industrial) customers can perform their own value activities better or cheaper. Analyzing the customers’ value chains should help identifying such activities. Moreover, he suggested to aim at preventing competition by building market entry barriers for other companies and by reducing market exit barriers for existing competitors. Moreover, he suggested to decrease competitors’ abilities to sell their products. He developed long lists of measures how to do this.

Company as a Set of Error-Free Processes

Total quality management (TQM) has its origins in quality management. Quality management originally was concerned with avoiding failures in the areas of incoming goods, production of safety-relevant parts of goods, and outgoing finished goods. Companies should be able to identify poor goods during the procurement, manufacturing, and selling process. Following the idea that are also manifold errors in other business areas including marketing, the principles of quality management were transferred to the entire company. The proponents of TQM came from engineering rather than business management. Two factors fostered the introduction of TQM: power asymmetries among industrial buyers and suppliers and desire for thinking in terms of law. At the end of the 90s, industrial buyers exerted pressure on their suppliers: the suppliers had to take part in certification processes to be considered as a supplier in the future as well. Second, law and TQM have in common that they strive for a higher density of regulation, and TQM facilitated introduction of legal views in companies.

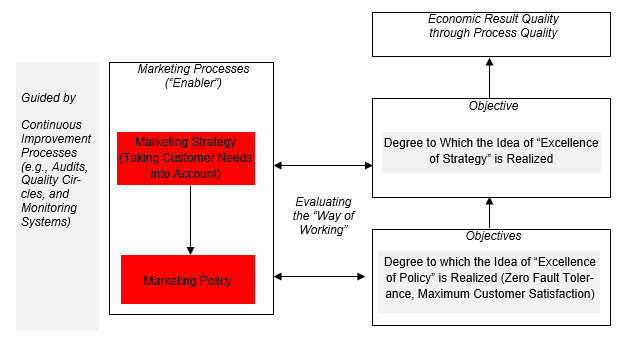

The concept of marketing within TQM could be visualized as follows.

According to TQM philosophy, the primary question is not what a good strategy is, but the question of how a good or error-free strategy can to be created. According to this approach, developers of the strategy are encouraged to look for “strategic benchmarks” and adopt such strategies. Such benchmarks are different companies whose strategy is presumably excellent. Regarding marketing policy, the company also is advised to look for and copy good practices from other companies; moreover, the company should also strive to continually improve processes between the company and its customers. Company employees are strongly engaged in processes to find better ways to achieve the goal of “excellence.”

Company as Investment for Equity Investors

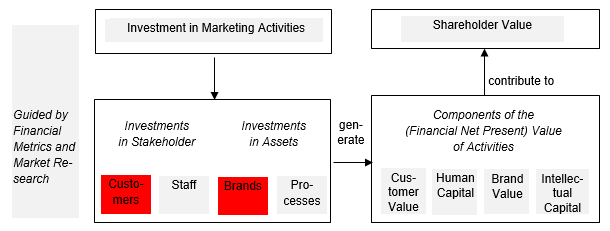

In the mid of the 90s, also the concept of value-based management (VBM) or shareholder value management emerged. At that time, supply and demand for equities, rather than goods and services, became more central to economic interest. The share prices became very “volatile,” i.e. “bubbles” were created, which today are connected with the New Economy and the US subprime market. Companies wished that the prices of their own shares would increase, in order to counter the danger of hostile takeover by competitors. Moreover, some company leaders promised that investments in their companies are very profitable. For instance, in February 2005, the former CEO of Deutsche Bank, Josef Ackermann, promised that shareholders will receive an annual return on equity of 25%. The shareholder value approach advocates that all major activities of a company are to be interpreted as investments. At the moment of investment, they cause cash outflow. The future cash inflows due to this outflow should result in a high return on investment for the shareholders (Rappaport 1999). In principle, a return on investment should be estimated for each activity. If this ROI is higher than the targeted return on investment, then the activity is justified; if it is lower than that, it is a matter of avoiding capital destruction.

Shareholder value management serves to maximize returns on investments of equity investors. Marketing activities are also understood as investments in this sense. Marketing activities cause customers to buy or the repurchase, improve sales people’s skills, increase the value of internally generated intangible assets (e.g., brands), and improve processes between companies and customers (e.g., enable online marketing). Value-based marketing cannot calculate the value increase of total equity arising from such types of activities and therefore relies on auxiliary measures to which the financial success of particular marketing activities could be more easily attributed. Investments in customers should be reflected in an increase in customer (lifetime) value, investments in brands in an increase in brand value, etc. Each of these “values” is the cash flow discounted to the present time, which is derived from the current and expected future cash inflows minus the cash outflows for financing the activities. Marketing department employees, as well as employees of other departments, have to justify, preferably by means of financial calculations, why their activities contribute to the financial net present value of the equity of shareholders or to adequately chosen auxiliary measures (e.g., customer value). The function of the management and all employees is exclusively to increase the value of the capital of the equity investors. The concept of value-based marketing can be visualized as follows:

Summary

Hopefully, these illustrations about what management and marketing are, are not too simplified. What we want to say is the following: Companies who sell industrially produced goods exist for 150 years. The challenges companies have to overcome often have changed over this time. Thus, many different management and marketing concepts have been developed that were tailored to provide special solutions. Evidently, companies could also combine different elements to arrive at their special management system. However, each management system presented here and numerous other systems have special advantages. For instance, companies who face many problems resulting from false decisions of employees are well advised to adopt TQM systems. Companies who have strong difficulties to get equity capital are advised to adopt VBM. Companies in duopoly where strong competition exists, are advised to consider Porter’s approach of market players.

We – the Wimu eV – address companies whose major challenge is sales to customer. For them, market-oriented management is the best option. In this sense, if your main challenge is customer-related, don’t be a hoarder. Prevent yourself from thinking in different systems of management such as they were described above and focus on market-oriented management, but be familiar with alternative options presented here.